From the depraved violence of the Boston Marathon bombing emerged a heartening human response. Local and nationwide sympathizers opened their hearts and homes to bombing victims, publicly sharing selfless offers of generosity — along with their names, phone numbers, e-mail addresses and neighborhoods in a Google document set up by The Boston Globe simply titled, “I have a place to offer.”

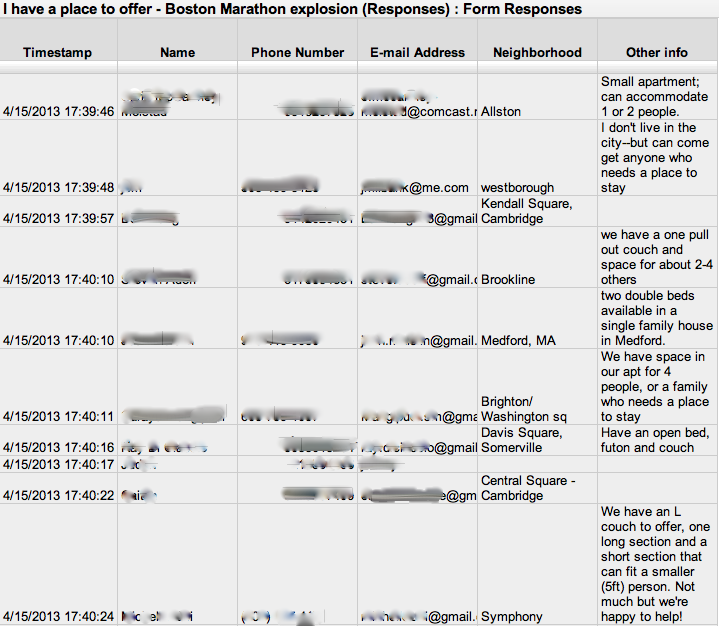

Here is an image of the beginning of the massive doc. We blurred out selected information to protect these Good Samaritans:

Entries ranged in simplicity from the first post, “Small apartment; can accommodate 1 or 2 people” at 5:39 p.m. EST to this one that offered quite a bit of information on the volunteer and even his friend:

I’m staying with a friend in Livermore, east bay area of San Francisco, and am out of work now for a couple of months. As a runner and a human being this is a great opportunity however since it gives me something away from the constant job hunt and allows me plenty of time to help in any way someone may need. Contact me by the most convenient method to you and allow me to do whatever I can to help.

The outpouring of offers spoke to the selflessness of so many in our society, but this “act of terror” inflamed our sensitivity over personal information. We weren’t the only ones.

“Sometimes, social media in the event of a crisis like this brings out both the best and dumbest in us,” Steve Quigley, a Boston University associate professor in the College of Communication told The Atlantic Wire. “I do think it’s moving to see how many people will respond generously, offering support and information. In some ways, it shines a spotlight on the best of us. It also perhaps gives low-hanging fruit to those who may represent the worst in us.”

As access and participation in digital spaces mushroom, more and more opportunities arise to spread personal information with insufficient safeguards. In this case, the Google doc is a click or tap away for anyone, whether a marathon victim or a criminal preying on personal information. Quigley thought it was “really risky” and would have preferred to see people provide their neighborhoods and e-mail addresses but hold their names and phone numbers. “I think people forget the medium they’re using and maybe even in a very best of instinct of trying to help somebody. It’s easy to rush in and provide more information than is wise to provide,” he said.

Granted much was public information, but a disaster like the Boston bombings creates an opportunity for scammers to capitalize on massive amounts of personal data. It suddenly becomes easier to juxtapose with information that location-based platforms like Foursquare make available, Quigley said.

Our concern – hopefully just paranoia – isn’t anything new. A Foursquare parody site pleaserobme.com launched in 2010 to raise awareness about over-sharing. “The danger is publicly telling people where you are. This is because it leaves one place you’re definitely not…. home,” the website says.

If that sounded like a stretch, this shouldn’t: scammers tweets. A much retweeted message came from the phony marathon account “@_BostonMarathon”, since deleted by Twitter, reading: “For every retweet we receive we will donate $1.00 to the #BostonMarathon victims #PrayForBoston.” As Benny Evangelista of The San Francisco Chronicle explains in his blog post:

Such tragedies always bring out the scammers trying to make a quick buck, and this is no exception. The Domains, a website that keeps track of Internet domain name news, reported that there were at least 70 “troubling” new domain names registered after the Boston bombings, “many that look like charitable domains that can be be used to raise money for the victims.”

Digital spaces, like public places, can harbor danger, but Quigley sees the glass as half full. “I’m not saying that these outlets are not being used to harm others but I have a general feeling that there’s more good coming from them than bad.”

We haven’t heard any reports of crime related to the Google doc sharing and sincerely hope we are being overly cautious in thinking such a positive use of social media could lead to harm.

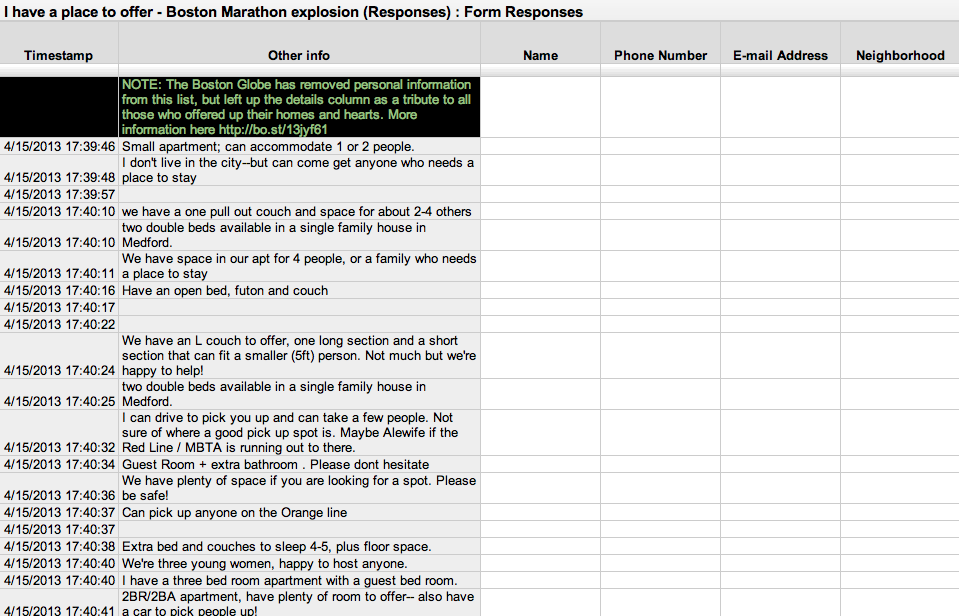

UPDATE: The Boston Globe took down personal information from the Google doc and stopped accepting submissions on Wednesday morning after receiving nearly 6,000 offers for help.

A row added at the top of the Google doc reads: “NOTE: The Boston Globe has removed personal information from this list, but left up the details column as a tribute to all those who offered up their homes and hearts.” The timestamps remain, as does “Other info” detailing what was being offered up, but the name, phone number, e-mail address and neighborhood are blanked out.

Again, excuse our paranoia, but we’re relieved.

Want to add to this story? Let us know in comments or share ideas for stories on the Open Wire.